Our governments are committing taxpayers to further debt as part of a planned recovery from the economic impacts of the coronavirus pandemic. Infrastructure spending is great for economic stimulus, but it has to be the right kind of infrastructure.

These are some of our largest public investments, so we want this public money to work a lot harder to create multiple rather than just singular benefits. As well as quickly providing jobs and the economic benefits of solving the problems of transport or energy supply, stimulus projects need to deliver broad, long-term community value, reduce inequality and help counter climate change.

The focus of fast-tracked infrastructure spending in the pandemic recovery should be many smaller-scale projects that provide these broader benefits. Hence these projects will provide greater value than the transport mega-projects that had already been proposed for economic stimulus.

For example, the high-speed rail project Labor has proposed will help decarbonise travel, but it won’t provide enough jobs in the short or medium term. Major road projects will cut commuting time for some drivers, but won’t provide widespread benefits or longer-term employment. New roads also increase emissions and often damage neighbourhoods.

Good infrastructure delivers broad benefits

Infrastructure projects are such significant economic engines they can incorporate community improvement without compromising their other outcomes.

The ways in which projects get planned and implemented hold the key. For example, projects should involve local businesses, give hiring preference to long-term unemployed people and use sustainable materials.

Infrastructure planning can integrate multiple functions. For example, water-management infrastructure (for drainage or flooding) can be designed to include open space, tree cover, recreation and cycleways. Streets can be designed as beautiful public spaces that include pedestrians, cyclists and cars, as well as tree canopy and water storage.

Good infrastructure used for employment creation and economic recovery looks like Roosevelt’s New Deal of the 1930s. These programs created a legacy of high-quality public infrastructure across the United States.

A “Green New Deal” approach in Australia could focus on smaller-scale projects, including:

- infrastructure to promote walking and cycling

- tree planting to reduce heat and store carbon

- land-management strategies to reduce fire and flood risks

- renewable energy infrastructure of all kinds

- improvements to public open spaces

- retrofitting and enhancing schools

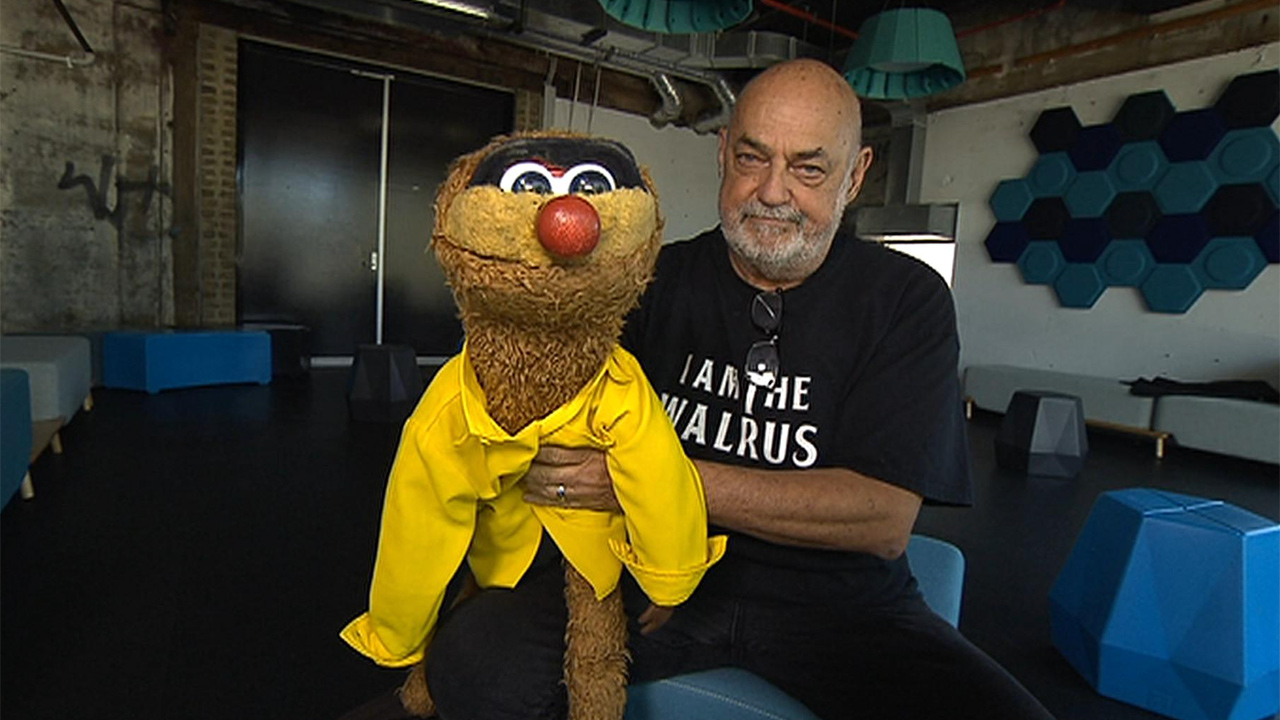

- multipurpose greenways.

This greenway traverses Sydney’s Inner West municipality.

These types of projects are fast to get going and labour-intensive. They can be implemented in both cities and regional areas. These projects can also build longer-term employment capacity and help with the transition of workers out of fossil fuel industry jobs.

Bigger isn’t necessarily better

The largest infrastructure projects, like those being proposed, are the riskiest in terms of cost blowouts and often deliver limited social and environmental value. In many instances their claimed economic value is also doubtful, as their costs are modelled inaccurately and their benefits and use are often vastly exaggerated.

One cause of cost blowouts is that governments are often reluctant to commit to spending in the early stages of major projects. This means commitments are often made before projects are well enough understood. Early spending to explore alternatives, understand impacts and consult widely can often realise projects more quickly and with more predictable outcomes that better serve the public interest.

The Morrison government is promoting the myth of fast-tracking through the cutting of red tape and green tape. This is not the key to faster project delivery. We have a decent system of development regulation, which attempts to balance the business interests of developers against the public good. The current crisis has illustrated very clearly the importance of the public values of liveability, preserving natural resources and easy access to open space and local centres.

We must hold all our infrastructure projects to higher standards. Robust planning and environmental regulation are crucial to maximise the public benefit of projects. Effective community engagement ultimately leads to smoother implementation and better outcomes. Projects that work within planning regulations move more swiftly into implementation than projects that try to bypass them.

In this pandemic crisis we have seen governments move fast and effectively to change policy and implement large-scale programs to benefit the community. The economic rebuilding forced on us by the pandemic is an opportunity to show the same agility to rethink our approach to infrastructure as an engine to uplift our communities and improve life for all citizens.

Written by Elizabeth Mossop. Republished with permission of The conversation.